Press Ups

Press Ups, aka Touch and Go, Basis 10 or Touch Down, is a 1974 board game by Yigal Bogoslavski, published at Invicta Games, among others. (GB patent 1524371)

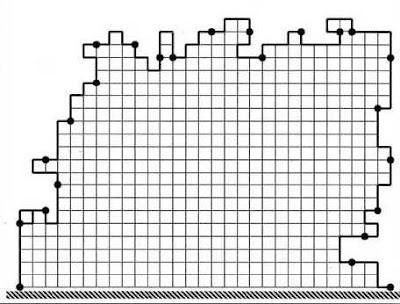

Players place their ten pieces (10 reds and 10 blues) like in the diagram, while 29 green pieces occupy the remaining squares. The 7x7 board allows pieces to be pressed down, which is just an aesthetical replacement for dropping pieces on empty squares.

The first player presses one friendly piece. For the rest of the game, each player must press some unpressed piece adjacent (orthogonal or diagonal) to the last pressed one.

When no more moves are possible, wins the player with more friendly pressed pieces.

Possible variants:

- change the King-like adjacency to a Knight-like, ie, the next piece to be pressed must be a knight's jump from the previous pressed piece.

- include a first phase where players, alternately, drop their friendly pieces on empty squares (they place all green pieces at the remaining squares)

A review on Games & Puzzles #43:

§

The move by blocking previous cells is a ludeme better known in Amazons (using a Queen-like adjacency). Alex Randolph's 1982 Plop is played with two Chess Knights on a 8x8 board, where each movement creates a wall on the initial square. The goal is to capture the single enemy Knight or stalemate the adversary. Around 2000 I submitted to The 32-Turn Challenge a Chess variant with this idea, The Knightliest Black Hole, where each move also removes an empty square from the board, but the game has several versions of the classical Knight. WAG's page about Slimetrail includes other abstract games with this type of move.

Jeux et Stratégie #37 presents another game with this idea, Numeration,

The first player marks the number 1 at an empty 5x5 board. Then, each player marks the successor of the previous number on an adjacent cell (orthogonal or diagonal), until the last possible move. That player scores the last number marked number, and sums to their total. The matches continue until one of the players reaches a predetermined goal.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)